Human immunome, bioinformatic analyses using HLA supermotifs and the parasite genome, binding assays, studies of human T cell responses, and immunization of HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice including novel adjuvants provide a foundation for HLA-A03 "..."

- Research

- Open Access

Human immunome, bioinformatic analyses using HLA supermotifs and the parasite genome, binding assays, studies of human T cell responses, and immunization of HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice including novel adjuvants provide a foundation for HLA-A03 restricted CD8+T cell epitope based, adjuvanted vaccine protective against Toxoplasma gondii

- Received: 28 September 2010

- Accepted: 3 December 2010

- Published: 3 December 2010

Abstract

Background

Toxoplasmosis causes loss of life, cognitive and motor function, and sight. A vaccine is greatly needed to prevent this disease. The purpose of this study was to use an immmunosense approach to develop a foundation for development of vaccines to protect humans with the HLA-A03 supertype. Three peptides had been identified with high binding scores for HLA-A03 supertypes using bioinformatic algorhythms, high measured binding affinity for HLA-A03 supertype molecules, and ability to elicit IFN-γ production by human HLA-A03 supertype peripheral blood CD8+ T cells from seropositive but not seronegative persons.

Results

Herein, when these peptides were administered with the universal CD4+T cell epitope PADRE (AKFVAAWTLKAAA) and formulated as lipopeptides, or administered with GLA-SE either alone, or with Pam2Cys added, we found we successfully created preparations that induced IFN-γ and reduced parasite burden in HLA-A*1101(an HLA-A03 supertype allele) transgenic mice. GLA-SE is a novel emulsified synthetic TLR4 ligand that is known to facilitate development of T Helper 1 cell (TH1) responses. Then, so our peptides would include those expressed in tachyzoites, bradyzoites and sporozoites from both Type I and II parasites, we used our approaches which had identified the initial peptides. We identified additional peptides using bioinformatics, binding affinity assays, and study of responses of HLA-A03 human cells. Lastly, we found that immunization of HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice with all the pooled peptides administered with PADRE, GLA-SE, and Pam2Cys is an effective way to elicit IFN-γ producing CD8+ splenic T cells and protection. Immunizations included the following peptides together: KSFKDILPK (SAG1224-232); AMLTAFFLR (GRA6164-172); RSFKDLLKK (GRA7134-142); STFWPCLLR (SAG2C13-21); SSAYVFSVK(SPA250-258); and AVVSLLRLLK(SPA89-98). This immunization elicited robust protection, measured as reduced parasite burden using a luciferase transfected parasite, luciferin, this novel, HLA transgenic mouse model, and imaging with a Xenogen camera.

Conclusions

Toxoplasma gondii peptides elicit HLA-A03 restricted, IFN-γ producing, CD8+ T cells in humans and mice. These peptides administered with adjuvants reduce parasite burden in HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice. This work provides a foundation for immunosense based vaccines. It also defines novel adjuvants for newly identified peptides for vaccines to prevent toxoplasmosis in those with HLA-A03 supertype alleles.

Keywords

- Cell Epitope

- Lipopeptide

- Immunize Mouse

- ELISpot Assay

- Peptide Pool

Background

Toxoplasmosis is a disease of major medical importance. Toxoplasma gondii causes congenital infections responsible for stillbirths and spontaneous abortions[1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. In addition, it causes neurologic disorders, uveitis, and systemic infections in immune-compromised patients. Toxoplasmic encephalitis is a cause of morbidity and mortality in those with congenital disease and persons with AIDS[6]. T. gondii is acquired by consumption of lightly cooked meat, especially lamb and pork contaminated with bradyzoites[7, 8] or by ingestion of food or water contaminated with oocysts containing sporozoites, which are the product of a sexual cycle in the intestine of the cat [8, 9].

Development of an effective vaccine would prevent this disease. Attenuated T. gondii tachyzoites (e.g., S48, TS-4, T-203, ΔRPS13)have been employed for live vaccinations of non-human animals[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Parasites attenuated by knockout of gene transcription recently have been proposed as a new type of attenuated vaccine candidate[13, 14, 15]. However, safety considerations may limit vaccination of humans with live organisms. Development of peptide-based vaccines created with epitopes which elicit IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells[16] is a promising strategy to mobilize the immune system against T. gondii in humans[16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Thus, an effort to create an immunosense epitope-based vaccine was initiated.

Recently, three peptide epitopes, KSFKDILPK (SAG1224-232), AMLTAFFLR (GRA6164-172), and RSFKDLLKK (GRA7134-142), were found by our group to elicit IFN-γ from peripheral blood mononuclear leukocytes (PBMCs) from T. gondii seropositive HLA-A03 supertype humans but not from PBMCs of T. gondii seronegative HLA-A03 supertype humans[18]. Herein, initially we designed 4 CD8+ T cell epitope containing vaccine formulations comprised of lipopeptides that incorporate PADRE as well as a novel oil-in-water emulsion that includes a specially formulated synthetic MLA derivative called GLA-SE[21, 22, 23, 24]. First, efficacy of various vaccine formulations consisting of the three previously identified CD8+ T cell peptides eliciting HLA-A*1101-restricted, CD8+T cell-mediated IFN-γ production in vitro from HLA-A*1101 mice was examined.

Then, in order to identify additional peptides from T. gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites and sporozoites of Type I and Type II strains that are effective in eliciting IFN-γ from HLA-A03 supertype restricted CD8+ T cells, the first step was to select proteins with biologic properties, such as being secreted, compatible with MHC Class I processing. Then, bioinformatic algorithms to identify HLA-A03 supertype bound peptides were utilized to find additional, novel T. gondii-derived, potential CD8+ T cell eliciting epitopes restricted by the HLA-A03 supertype. We screened peptides from tachyzoite, bradyzoite and sporozoite proteins (GRA10, GRA15, SAG2C, SAG2D, SAG2X, SAG3, SRS9, BSR4, SPA, MIC) of the type II T. gondii strain, ME49, searching for those with high binding scores in a bioinformatic analysis (IC50 < 50 nM) and then in binding assays. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from seropositive and seronegative persons were tested for response to these peptides using an IFN-γ ELISpot assay. These latter studies were performed to attempt to identify other peptides that would be promising candidates for inclusion in a multi-epitope, next generation immunosense vaccine. Then, information obtained from testing the first three peptides studied was used to guide formulation and administration of a peptide pool. This pool included the first three peptides identified earlier and tested in the initial experiments combined with the newly identified peptides that elicited IFN-γ from human HLA-A03 supertype restricted CD8+ T cells. All the peptides in this pool were tested with a universal T helper epitope called PADRE and a new, promising adjuvant called GLA-SE with Pam2Cys in HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice. Capacity to induce IFN-γ production by spleen CD8+ T cells, and to protect against parasite burden following subsequent challenge were determined. For parasite challenge, a luciferase transfected Type II Prugneaud parasite was administered, followed by luciferin administration and imaging with a Xenogen camera system a week later. This allows detection and quantization of bioluminescent parasites as a biomarker to assess efficacy of immunizations in protection.

Results

Construction of CD4-CD8 lipopeptide based candidate vaccine

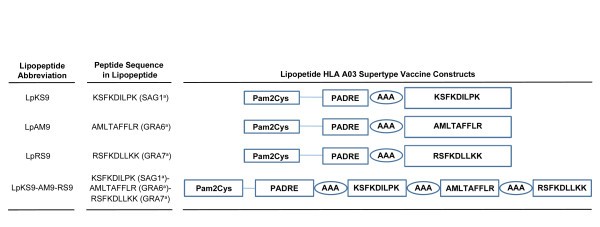

Schematic representation of the synthetic lipopeptide immunogens used in this study. The C-terminal end of a promiscuous CD4+ T cell peptide epitope (PADRE) was joined in sequence with the N-terminal end of one of three different T. gondii CD8 T cell epitopes: SAG1224-232 (A), GRA6164-172 (B); GRA7134-142 (C) or three epitopes linked together (D) with a three alanine linker. The N-terminal end of each resulting CD4-CD8 peptide was extended by a lysine covalently linked to one molecule of palmitic acid. This results in a four lipopeptides construct.

The abbreviation Lp is used throughout the manuscript whenever the lipopeptide (Lp) has been studied. When there is a mixture of components or undivided components they are named individually. Sequence of PADRE is AKFVAAWTLKAAA. Structure of Pam2Cys is PAM2KSS. a = abbreviation for name of protein from which peptide is derived.

Immunogenicity of lipopeptides in HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice

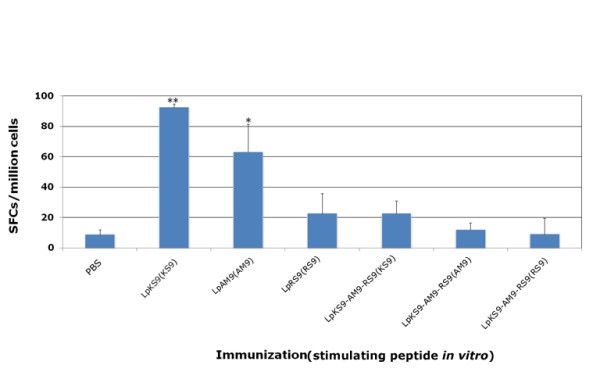

HLA-A*1101 mice immunized with lipopeptides. Mice were immunized with lipopeptides: LpKS9, LpAM9, LpRS9 and LpKS9-AM9-RS9 which were shown in Figure 1. The mice were immunized twice at intervals of three weeks. Ten to fourteen days after the last immunization, spleen cells were separated from immunized mice and stimulated by appropriate peptides in an ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data presented are averages of three independent replicate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Comparison of vaccination with different formulations of peptides

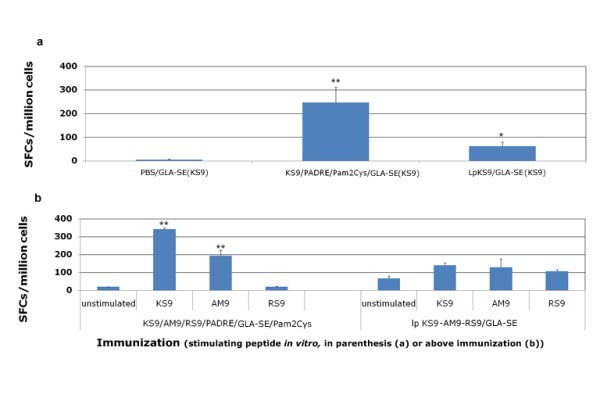

Lipopeptides vaccine compared with peptide pool vaccine. HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice were immunized either with lipopeptides or a mixture of peptides plus GLA-SE and Pam2Cys. LpKS9 and KS9/PADRE/GLA-SE/Pam2Cys (Figure 3a), LpKS9-AM9-RS9 and KS9/AM9/RS9/PADRE/GLA-SE/Pam2Cys (Figure 3b) were used as immunogens. For the lipopeptide immunizations, the mice were vaccinated twice at intervals of three weeks. For the immunizations containing individual components including the same peptides, the mice were vaccinated three times at intervals of two weeks. Ten to fourteen days after the last immunization, spleen cells were separated from immunized mice and stimulated by the appropriate peptide in an ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data presented are a representative example from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Effects of adjuvant on immunogenicity of pooled peptide vaccination

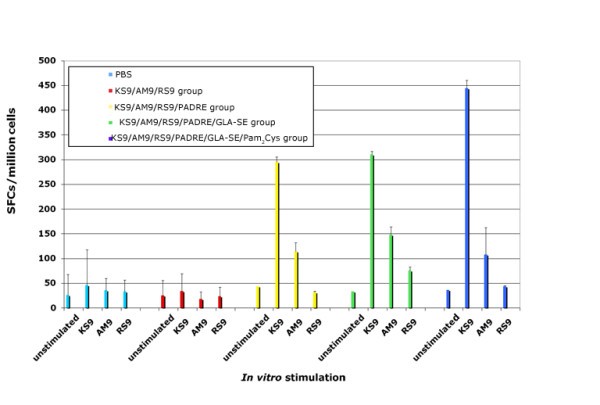

HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice immunized with peptide pool and adjuvants. Mice were immunized with PBS, peptide pool, peptide pool with PADRE, peptide pool with PADRE in GLA-SE, peptide pool with PADRE and Pam2Cys in GLA-SE. Splenic T cells were isolated 10-14 days post-immunization and exposed to each peptide in an ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assay.

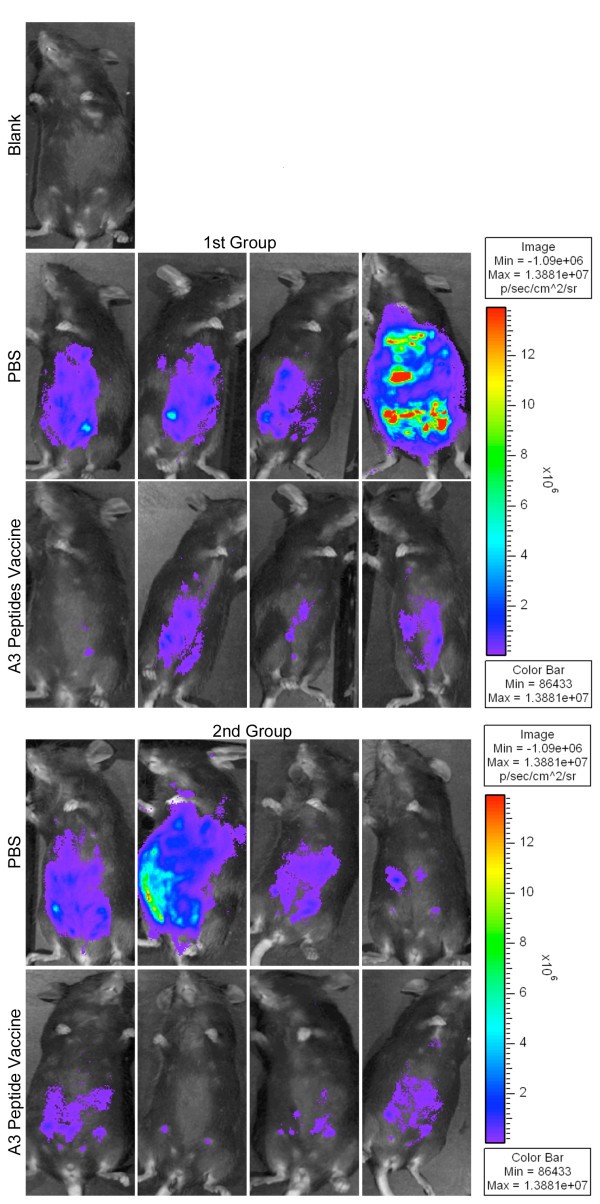

Vaccination with peptide pools and adjuvants protects mice against type II parasite challenge

In vivoprotection demonstrated with imaging using Xenogen camera. HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice immunized with peptide pool and adjuvants were protected compared to control mice inoculated with PBS when they were challenged with 10,000 Prugneaud strain (Fluc)-T. gondii luciferase expressing parasites. There were a total of 5-9(usually 4-5 per group) mice tested in each control or immunization group. Differences between control and immunization groups were significant(p < 0.0064 using natural log transformed data and two-sample t test).

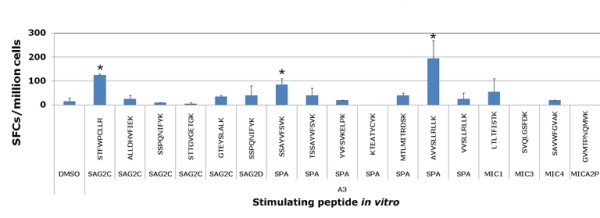

Identification of new candidate T. gondii specific HLA-A*1101-restricted epitopes

Peptides, their affinity for HLA-A*1101, and their immunogenicity in humans and for transgenic mice

Peptide Sequences |

Protein1 |

Affinity2 HLA-A*1101 |

Elicit IFN-γ3 in |

Immunogenicity4 in mice |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Seropositive human |

Seronegative human |

||||

KSFKDILPK |

SAG1224-232 |

54 |

+ |

- |

+ |

AMLTAFFLR |

GRA6164-172 |

3.6 |

+ |

- |

+ |

RSFKDLLKK |

GRA7134-142 |

14 |

+ |

- |

- |

STFWPCLLR |

SAG2C13-21 |

10 |

+ |

- |

+ |

SSAYVFSVK |

SPA250-258 |

10 |

+ |

- |

+ |

AVVSLLRLLK |

SPA89-98 |

34 |

+ |

- |

+ |

Predicted peptide candidates utilized for screening CD8+ T cells1

HLA-A*1101 |

ANTIGEN |

PEPTIDE SEQUENCES |

LENGTH |

LOCATION |

PREDICTED IC50 nM |

POOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA15 |

STSPFATRK |

9 |

152-160 |

5 |

P1 |

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA15 |

ASTSPFATRK |

10 |

150-159 |

18.2 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA10 |

AAAATPGLPK |

10 |

568-577 |

9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA10 |

AAATPGLPK |

9 |

569-577 |

13.2 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA10 |

GVPAVPGLLK |

10 |

507-516 |

17 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

GRA10 |

SVVEENTMAK |

10 |

865-874 |

25.1 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2C |

STFWPCLLR |

9 |

13-21 |

9.3 |

P2 |

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2C |

ALLDHVFIEK |

10 |

231-240 |

11.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2C |

SSPQNIFYK |

9 |

290-298 |

12.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2C |

STTGVGETGK |

10 |

163-172 |

28.4 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2C |

GTEYSLALK |

9 |

136-144 |

35.4 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2D |

SSPQNIFYK |

9 |

122-130 |

12.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2D |

ALLEHVFIEK |

10 |

63-72 |

20.2 |

P3 |

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2D |

SSAQTFFYK |

9 |

290-298 |

1.8 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2D |

TVYFSCDPK |

9 |

154-162 |

5.3 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG2D |

PSSAQTFFYK |

10 |

289-298 |

17.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG3 |

VVGHVTLNK |

9 |

80-88 |

15.4 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SAG3 |

KQYWYKIEK |

9 |

145-153 |

19.3 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SRS9 |

TTCSVLVTVK |

10 |

357-366 |

20.6 |

P4 |

HLA-A*1101 |

SRS9 |

AAASVQVPLK |

10 |

140-149 |

29.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SRS9 |

AIQSQKWTLK |

10 |

169-178 |

35 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

BSR4 |

TTRFVEIFPK |

10 |

284-293 |

10.3 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

BSR4 |

VSGSLTLSK |

9 |

83-91 |

21.1 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

SSAYVFSVK |

9 |

250-258 |

9.3 |

P5 |

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

TSSAYVFSVK |

10 |

249-258 |

12.2 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

YVFSVKELPK |

10 |

253-262 |

18 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

KTEATYCYK |

9 |

262-270 |

18.4 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

MTLMITRDSK |

10 |

195-204 |

25.5 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

AVVSLLRLLK |

10 |

89-98 |

6.5 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

SPA |

VVSLLRLLK |

9 |

90-98 |

7.2 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

MIC1 |

LTLTFISTK |

9 |

338-346 |

13.8 |

P6 |

HLA-A*1101 |

MIC3 |

SVQLGSFDK |

9 |

32-40 |

12.9 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

MIC4 |

SAVWFGVAK |

9 |

16-24 |

17.2 |

|

HLA-A*1101 |

MICA2P |

GVMTPNQMVK |

10 |

63-72 |

14.3 |

New peptides tested with PBMCs from HLA-A03 seropositive and seronegative donors. Then Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from seropositive T. gondii donors were tested for response to these predicted HLA-A03 supertype restricted CD8+ T cell epitope individual peptides by using IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Peptides that induced significant IFN-γ spot formation compared to DMSO are denoted by an asterisk. *, P < 0.05.

MHC binding affinity assay for peptides that were identified with predictive algorithms for HLA-A03 supertype

HLA-A03-SUPERTYPE |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

PEPTIDE SEQUENCE |

LENGTH |

PROTEIN |

POSITION |

HLA-A*0301 |

HLA-A*1101 |

HLA-A*3001 |

HLA-A*3101 |

HLA-A*3301 |

HLA-A*6801 |

SUPERTYPE ALLELES BOUND |

STFWPCLLR |

9 |

SAG2C |

13-21 |

22 |

10 |

1272 |

1.2 |

3.4 |

0.97 |

5 |

SSAYVFSVK |

9 |

SPA |

250-258 |

12 |

10 |

1826 |

97 |

181 |

2.1 |

5 |

AVVSLLRLLK |

10 |

SPA |

89-98 |

17 |

34 |

8.1 |

1296 |

1100 |

94 |

4 |

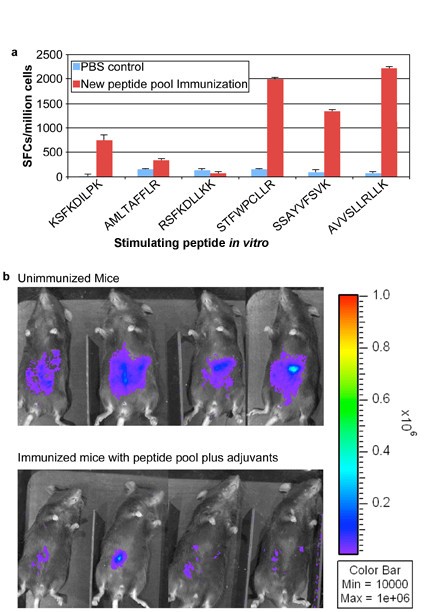

Vaccination with peptide pools including newly identified peptides and adjuvants elicits IFN-γ and provides more protection to mice against Type II parasite challenge

Addition of peptides to pool robustly protects HLA-A*1101 mice against Type II parasite challenge. HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice were immunized with PBS (controls) or peptide pool with PADRE and Pam2Cys in GLA-SE. Splenic T cells were isolated 10-14 days post immunization and exposed to each peptide in an ex vivo IFN-γ ELISpot assay (Figure 7a). HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice immunized with peptide pool and adjuvants were protected compared with control mice inoculated with PBS when they were challenged with 10,000 Pru (Fluc)-T. gondii luciferase expressing parasites (Figure 7b). Mice were immunized and in a subgroup immune function was studied at the same time as the challenge shown was performed. Differences between control and immunized mice were significant (p < 0.0064 using natural log transformed data and two-sample t test).

Mice were challenged 2 weeks after the last immunization. They were imaged five days after they had been challenged with 10,000 Pru (Fluc) using a Xenogen in vivo imaging system. As shown in the initial experiment in Figure 7b, the numbers of luciferase expressing parasites in immunized HLA-A*1101 mice were significantly reduced compared to the numbers of parasites in unimmunized mice. Results were mean[standard deviation](median) 2.5[1](2.3) million for nonimmunized mice versus.6[.3](.5)million for immunized mice. With natural log transformed data, mean[standard deviation} was.9 [.4] for nonimmunized mice versus -.6[.4] for immunized mice; p < 0.0025 using natural log transformed data and two-sample t test.

Population Coverage prediction

Prediction of population coverage

Class I |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Population/Area |

Coverage a |

Average hit b |

PC90 c |

Australia |

28.90% |

1.30 |

0.14 |

Europe |

41.46% |

0.98 |

0.17 |

North Africa |

27.32% |

0.45 |

0.14 |

North America |

11.29% |

0.24 |

0.11 |

North-East Asia |

18.86% |

0.74 |

0.12 |

Oceania |

34.09% |

1.69 |

0.15 |

Other |

22.13% |

0.59 |

0.13 |

South America |

0.42% |

0.00 |

0.10 |

South-East Asia |

37.73% |

1.84 |

0.16 |

South-West Asia |

34.29% |

1.09 |

0.15 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

13.14% |

0.23 |

0.12 |

Average (Standard deviation) |

24.51% (12.06%) |

0.83 (0.58) |

0.14 (0.02) |

Discussion

In this study, we first evaluated immunization of HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice with either mixtures of peptides or lipopeptides derived from three identified T. gondii specific HLA-A*1101 restricted CD8+ T cell epitopes emulsified in 3-deacylated monophosphoryl lipid A(GLA-SE) adjuvant. Immunizations of transgenic mice with a mixture of CD8+ epitope peptide pools plus PADRE and adjuvants were able to induce splenocyte to produce IFN-γ and to protect against challenge with high numbers of Type II parasites.

Conjugation of CD8+ T cell determinants to lipid groups is known to enhance specific cell-mediated responses to target antigens in experimental animals and humans[25, 26, 27, 28, 29], although mechanisms whereby immunity is achieved remains poorly understood. Lipopeptides hold several advantages over other conventional vaccine formulations; for instance, they are self-adjuvanting and display none of the toxicity-associated side effects of other Th1-inducing adjuvant systems. In our work, transgenic mice that were immunized with three short lipopeptide vaccines had T cells that produced IFN-γ. Among them the lipopeptide vaccine formulated with KS9 or AM9 stimulated higher IFN-γ production than the lipopeptide vaccine formulated with RS9. Unexplained and variable responses have been observed to high affinity binding peptides in other models, e.g., studies of Livingstone, Alexander, Sette et al with Lassa fever virus. It will be of interest to better understand possible mechanisms for such lack of response in future studies. However, the lipopeptides with three epitope peptides linked together with alanine spacers did not stimulate an IFN-γ response by splenocytes from immunized mice when the splenocytes subsequently were exposed to each of the peptides in vitro. The reason why the lipopeptides with the three linked peptides did not work well in the transgenic mice might be related to a frame shift caused by the linkers that altered the response to the original peptides rather than the alanines functioning for the intended purpose of introducing a cleavage motif. The three linker "AAA'' between the peptides had previously been demonstrated in other systems to result in sensitization to each linked peptide. However, surprisingly, it did not appear to work well herein.

Because the three linked peptides in the lipopeptide formulation were not effective and we had found that a mixture of the components with a single peptide was as or more robust than the lipopeptide, we tried this approach with the three peptides that had been included in the linked lipopeptide with the universal helper CD4+ T cell peptide, PADRE, and adjuvants as described below. The response was robust both in vitro and in vivo (Figures 4 and 5).

Some studies have shown palmitoylated lipopeptide constructs to elicit long-lived, protective cellular responses against a variety of pathogens, including Hepatitis B virus (HBV), influenza virus, and Plasmodium falciparum [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Our work herein shows that mice immunized with mixture of CD8+ and CD4+ eliciting peptides and lipid Pam2Cys emulsified in GLA-SE elicited higher IFN-γ production than mice immunized with lipopeptides constructed with the same components of CD4+ and CD8+ eliciting peptides, and Pam2Cys. The approach using cocktails of non-covalently linked lipid mixed to helper T lymphocytes(HTL) and CD8+T cell (cytolytic T lymphcyte[CTL] and IFN-γ eliciting) epitopes for simultaneous induction of multiple CD8+T specificities would have significant advantages in terms of ease of vaccine development.

HTL responses are crucial for the development of CD8+T responses, at least in the case of lipidated covalently or non-covalently linked HTL-CTL epitope constructs formulated in PBS. Several previous studies have illustrated a role for CD4+ responses for development of CD8+CTL responses, both in humans and in experimental animals[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. The inclusion of PADRE, a synthetic peptide that binds promiscuously to variants of the human MHC class II molecule DR and is effective in mice, also augmented CD8+ T cell effector functions by inducing CD4+ T helper cells[30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. Both CD4+ and CD8+ epitopes were targeted in order to drive a protective immune response[34, 35].

Adjuvanting antigens contributes to the success of vaccination. An example herein is that 3-deacylated monophosphoryl lipid A(GLA-SE), a detoxified derivative of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Salmonella minnesota R595 was a potent adjuvant. This GLA-SE is a novel adjuvant which was formulated in an emulsion[21, 22, 23, 24]. This is a Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist that is a potent activator of Th1 responses [21, 22, 23, 24]. It has been used as an adjuvant in human vaccine trials for several infectious disease and malignancy indications. It has been very effective as an adjuvant providing CD4+ T cell help for immunizations against other protozoan infections such as leishmaniasis [21, 22, 23, 24]. In our study, a robust response was observed when GLA-SE was included in preparation for immunization of mice. Pam2Cys (S-[2,3-bis(palmitoyloxy)propyl]cysteine) is a lipid component of macrophage-activating lipopeptide. Pam2Cys binds to and activates dendritic cells by engagement of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2)[24]. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) function as pattern-recognition receptors in mammals[36]. We have found that both TLR2 and TLR4 receptors participate in human host defense against T. gondii infection through their activation by GPIs and GIPLs(Melo, Hargrave, Miller, Blackwell, Gazinelli, McLeod et al, in preparation, 2010). TLR2 and TLR4 likely work together with other MyD88-dependent receptors, including other TLRs, to elicit an effective host response against T. gondii infection[36]. In our study, there was a slightly more robust response observed when Pam2Cys was co-administered for some peptides, but not all of them.

The goal of the present study was to identify HLA-restricted epitopes from T. gondii and evaluate whether they could provide protection against parasite challenge measured as protection against a luciferase producing Type ll parasite using a Xenogen camera system. In the future, additional more detailed studies involving analyses over longer times, other strains of the parasite and challenge with life cycle stages, evaluation of multiple organs including eye and brain, studies of protection in congenital infections, comparisons of delivery of these peptides as DNA encoding them versus other formulations. This future work will follow up and extend these intitial studies of reduction of parasite burden seen in Figures 5 and 7.

Various peptide-based approaches to induction of IFN-γ responses were evaluated as part of ongoing efforts to develop immunosense vaccines for use in humans with each of the supermotifs which would in total include more that 99% of the human population worldwide. Robust protection was achieved in the HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice challenged with Type II parasites following immunizations. In order to identify additional peptides from T. gondii that were present in tachyzoites or bradyzoites[37, 38] or sporozoites of Type I and II strains and elicited IFN-γ from HLA-A03+ supertype (which includes the HLA*1011 allele) restricted CD8+ T cells, bioinformatic algorithms were utilized to identify novel, T. gondii-derived, epitopes restricted by the HLA-A03 supertype. Then PBMC cells were tested to determine whether the peptides elicited IFN-γ from human CD8+ T cells from seropositive persons. This was intended to collectively provide broad coverage for the human population with HLA-A03 supertype worldwide. The additional peptides we identified as immunogenic for human peripheral blood cells were also robust in eliciting IFN-γ from splenocytes of HLA-A*1101 mice and protection when used to immunize these mice. These findings will facilitate development of an immunosense epitope-based vaccine for human use.

Conclusion

A human immunome-based and parasite genome based bioinformatices approach was used to define candidate HLA-A03 supertype restricted peptides. Immunogenicity of a group of T. gondii HLA-A03 supertype restricted peptides, and therefore the proteins from which they are derived, for immune humans and HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice was demonstrated. These peptides elicit interferon-γ production by human CD8+T cells. They also elicit interferon γ production by mouse splenocytes when utilized to immunize HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice with a lipopeptide with a universal CD4+ T cell eliciting epitope, PADRE, or in peptide pools with PADRE, Pam2Cys and GLA-SE, a novel adjuvant. Immunization studies demonstrate the need for and the efficacy of adjuvants in immunization of these HLA transgenic mice. Immunogenic peptides included KSFKDILPK (SAG1224-232); AMLTAFFLR (GRA6164-172); and RSFKDLLKK (GRA7134-142); STFWBCLLR (SAG2C13-21); SSAYVFSVK (SPA250-258); and AVVSLLRLLK (SPA89-98). The studies herein provide a foundation for immunosense based vaccines to prevent toxoplasmosis in those with the HLA-A03 supertype and information about how they can be adjuvanted.

Methods

Peptides and lipopeptides

HLA-A03 supertype CD8+ T cell epitopes included: KSFKDILPK (SAG1224-232), AMLTAFFLR (GRA6164-172), and RSFKDLLKK (GRA7134-142). PADRE (AKFVAAWTLKAAA) was the universal CD4 helper peptide used in vaccine constructs. Pam2Cys (Pam2-KSS) also was included. Lipopeptide constructs used in this study are shown in Figure 1. Peptides and lipopeptides were synthesized by Synthetic Biomolecules, San Diego at > 90% purity. Additional HLA-A03 supertype bound peptides and their initial grouping into pools for in vitro studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A TLR4 agonist, a GLA-SE adjuvant, was synthesized by the Infectious Diseases Research Institute (Seattle, Washington) as a stable oil-in-water emulsion. AMLTAFFLR (GRA6 164-172) and additional new peptides were first dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in PBS.

Mice

HLA-A*1101/Kb transgenic mice were produced at Pharmexa-Epimmune (San Diego, CA) and bred at the University of Chicago. These HLA-A*1101/Kb transgenic mice express a chimeric gene consisting of the 1 and 2 domains of HLA-A*1101 and the 3 domain of H-2Kb, and were created on a C57BL/6 background. For each test, we used 4-5 mice for each group. Each experiment was repeated 2 to 3 times. Experiments in Figure 7b were performed including a subgroup analyzed for immune response in parallel with a subgroup in the challenge shown. All studies were conducted with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Chicago.

Parasites

Transgenic T. gondii used for in vivo challenges was derived from Type II Prugniaud (Pru) strain and expresses the firefly luciferase (FLUC) gene constitutively by tachyzoites and bradyzoites. It was created, and kindly provided by S. Kim, J. Boothroyd and J. Saeij(Stanford University) and was maintained and utilized as previously described[18, 37, 39].

Immunizations and challenge

To evaluate peptide immunogenicity, HLA-A*1101 transgenic mice were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) at the base of the tail using a 30-gauge needle with single peptides or a mixture of CD8+ T cell peptides (50 μg of each peptide per mouse) and PADRE (AKFVAAWTLKAAA) emulsified in 20 μg of GLA-SE (TLR4 agonist) with or without Pam2Cys. Pam2Cys concentration was 5 mg/ml. For immunization with lipopeptides, HLA-A*1101 mice received 20 nmol lipopeptide dissolved in PBS or emulsified in GLA-SE. As controls, mice were injected with PBS or PBS/GLA-SE. For the lipopeptide immunizations, the mice were vaccinated twice at intervals of three weeks. For the peptide immunizations, mice were immunized three times at intervals of two weeks. For challenge studies, mice were immunized with peptide emulsions and challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) 14 days post-immunization using 10,000 Type II parasites.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

Mice infected with 10,000 Pru-FLUC tachyzoites were imaged 7 days post-challenge using the in vivo imaging system (IVIS; Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Mice were injected i.p. with 200 μl of D-luciferin, anesthetized in an O2-rich induction chamber with 2% isoflurane, and imaged after 12 minutes. Photonic emissions were assessed using Living image® 2.20.1 software (Xenogen). Data are presented as pseudocolor representations of light intensity and mean photons/region of interest (ROI). All mouse experiments were repeated at least twice. There were 4-5 mice for each group. In the experiment in Figure 7b a subgroup of mice was used for studying immune response in parallel with the subgroup in the challenge shown.

ELISpot assay

Murine splenocytes

Mice were euthanized 7 to 14 days after immunization. Spleens were harvested, pressed through a 70 μm screen to form a single-cell suspension, and depleted of erythrocytes with AKC lysis buffer (160 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 100 M EDTA). Splenocytes were washed twice with Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and resuspended in complete RPMI medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-GlutaMax [Invitrogen], 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 M -mercaptoethanol, and 10% FCS) before they were used in subsequent in vitro assays. Peptide concentration was 20 mg/ml and 0.20 μl was used per well. ELISpot assays with murine splenocytes were performed using α-mouse IFN-γ mAb (AN18) and biotinylated α-mouse IFN-γ mAb (R4-6A2) as the cytokine-specific capture antibodies. Antibodies were monoclonal antibodies. 5 × 105 splenocytes were plated per well.

Human PBMC

PBMC were obtained, HLA haplotype was determined, and they were processed and cryopreserved as described[18]. ELISpot assays with human PBMCs were similar to those with murine splenocytes but used α-human IFN-γ mAb (1-D1K) with biotinylated α-human IFN-γ mAb (7B6-1) with 2 × 105 PBMCs per well. All antibodies and reagents used for ELISpot assays were from Mabtech (Cincinnati, OH). Antibodies were monoclonal antibodies. Both murine and human cells were plated in at least 3 replicate wells for each condition. Results were expressed as number of spot forming cells (SFCs) per 106 PBMCs or per 106 murine splenocytes.

Bioinformatic predictions and MHC-peptide binding assays

Protein sequences derived from GRA10, GRA15, SAG2C, SAG2D, SAG2X, SAG3, SRS9, BSR4, SPA, and MIC were analyzed for CD8+ T cell epitopes based on predicted binding affinity to HLA-A03 supertype molecules using ARB algorithms from immunoepitope database (IEDB) http://www.immuneepitope.org[40, 41]. A total of 34 unique peptides IC50 < 50 nM of all ranked nonameric peptides were selected. All protein sequences were from ToxoDB 5.1.

Quantitative assays to measure binding of peptides to HLA class I molecules are based on inhibition of binding of radiolabeled standard peptide. Assays were as described[42]. Concentration of peptide yielding 50% inhibition of binding of radiolabeled probe peptide (IC50) was calculated. Under conditions used, where [radiolabeled probe] < [MHC] and IC50 ≥ [MHC], measured IC50 values are reasonable approximations of true K d values[43, 44].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses for all in vitro assays were performed using 2-tailed student's T test. Natural log transformed data and two-sample t test were used to analyze data shown in Figures 5 and 7b. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Peptides were considered immunogenic in mice if they induced IFN-γ spot formation from immunized mice that were significant (P < 0.05) compared with spot formation from control mice. All mouse experiments were repeated at least twice. There were 4-5 mice for each group. The experiment in Figure 7b determined immune response and imaged mice in parallel.

Declarations

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Oseroff for helpful suggestions, K. Wroblewski for assistance with statistical analyses, P. Terasaki for HLA-typing, J. Boothroyd, J. Saeij, and S. Kim for the luciferase expressing parasite, N. Blanchard and N. Shastri for sharing pre-publication data and other suggestions, S. Reed for adjuvants, and families and collaborating physicians/scientists in the NCCCTS who made this work possible. We gratefully acknowledge support of this work by gifts from the Fin Charity Trust, R. Blackfoot, R. Thewind, A. Akfortseven, S. Gemma, S. Jackson, A.K. Bump, the Rooney Aldens, the Dominique Cornwell and Peter Mann Family Foundation, the Alison F. Engel and Peter E. Engel Charitable Fund, Jack M. and Donna L. Greenberg Philanthropic Fund, the Morel, Rosenstein, Kapnick, Taub, Daley-Conroy, Schilling, Greenberg, Dunphy, Zorek, Munroe, and Kiewit families, and Toxoplasmosis Research Institute. This work also was supported by DMID-NIAID U01 AI77887, UR01 AI0433228, R01 AI071319, (RM), the China scholarship Council(CH), a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (No. 30700693)(CH), and The Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation(RM). The funding sources had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authors’ Affiliations

References

- Remington JS, McLeod R, Thulliez P, Wilson C, Desmonts G: Congenital Toxoplasmosis. In Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. 7th edition. Edited by: Remington JS, Klein J, Wilson C. Philadelphia: W.B Saunders; 2010:in press.Google Scholar

- McLeod R, Mack D, Foss R, Boyer K, Withers S, Levin S, Hubbel J: Levels of pyrimethamine in sera and cerebrospinal and ventricular fluids from infants treated for congenital toxoplasmosis. Antimicrob Ag Chemother 1992, 36:1040–8.Google Scholar

- McLeod R, Kieffer F, Sautter M, Hosten T, Pelloux H: Why prevent, diagnose and treat congenital toxoplasmosis? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104:320–344.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- McAuley J, Boyer KM, Patel D, Mets M, Swisher C, Roizen N, Wolters C, Stein L, Stein M, Schey W, Remington J, Meier P, Johnson D, Heydemann P, Holfels E, Withers S, Mack D, Brown C, Patton D, McLeod R: Early and longitudinal evaluations of treated infants and children and untreated historical patients with congenital toxoplasmosis: the Chicago Collaborative Treatment Trial. Clin Infect Dis 1994, 18:38–72.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Phan L, Kasza K, Jalbrzikowski J, Noble AG, Latkany P, Kuo A, Mieler W, Meyers S, Rabiah P, Boyer K, Swisher C, Mets M, Roizen N, Cezar S, Sautter M, Remington J, Meier P, McLeod R, Toxoplasmosis Study Group: Longitudinal study of new eye lesions in children with toxoplasmosis who were not treated during the first year of life. Am J Ophthalmol 2008, 146:375–84.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Luft BJ, Remington JS: Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 1992, 15:211–222.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Jacobs L: Toxoplasma gondii: parasitology and transmission. Bull N Y Acad Med 1974, 50:128–145.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dubey JP: The History and Life Cycle of Toxoplasma gondii . In Toxoplasma gondii: The Model Apicomplexan: Perspectives and Methods. Edited by: Weiss LM, Kim K. London: Academic Press; 2007:1–17.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boyer K, Holfels E, Roizen N, Swisher C, Mack D, Remington J, Withers S, Meier P, Karrison T, McLeod R: Risk factors for Toxplasma gondii infection in mothers of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis: implications for prenatal management and screening. AJOG 2005, 192:564–71.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- McLeod R, Frenkel JK, Estes RG, Mack DG, Eisenhauer P, Gibori G: Subcutaneous and intestinal vaccination with tachyzoites of Toxoplasma gondii and acquisition of immunity to peroral and congenital Toxoplasma challenge. J Immunol 1988, 140:1632–7.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Buxton D, Thomson K, Maley S, Wright S, Bos HJ: Vaccination of sheep with a live incomplete strain (S48) of Toxoplasma gondii and their immunity to challenge when pregnant. Vet Rec 1991, 129:89–93.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lu F, Huang S, Kasper LH: The temperature-sensitive mutants of Toxoplasma gondii and ocular toxoplasmosis. Vaccine 2009, 27:573–580.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Mévélec MN, Ducournau C, Bassuny Ismael A, Olivier M, Sèche E, Lebrun M, Bout D, Dimier-Poisson I: Mic1–3 Knockout Toxoplasma gondii is a good candidate for a vaccine against T. gondii -induced abortion in sheep. Vet Res 2010, 41:49.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gigley JP, Fox BA, Bzik DJ: Cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii develops primarily by local Th-1 host immune responses in the absence of parasite replication. J Immunol 2009, 182:1069–1078.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Hutson SL, Mui E, Kinsley K, Witola WH, Behnke MS, El Bissati K, Muench SP, Rohrman B, Liu SR, Wollmann R, Ogata Y, Sarkeshik S, Yates JR III, McLeod R: T. gondii RP Promoters & Knockdown Reveal Molecular Pathways Associated with Proliferation and Cell-Cycle Arrest. PLoS ONE 2010,5(11):e14057.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blanchard N, Gonzalez F, Schaeffer M, Joncker NT, Cheng T, Shastri AJ, Robey EA, Shastri N: Immunodominant, protective response to the parasite Toxoplasma gondii requires antigen processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Immunol 2008, 9:937–944.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bui HH, Sidney J, Li W, Fusseder N, Sette A: Development of an epitope conservancy analysis tool to facilitate the design of epitope-based diagnostics and vaccines. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8:361.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tan TG, Mui E, Cong H, Witola WH, Montpetit A, Muench SP, Sidney J, Alexander J, Sette A, Grigg M, Maewal A, McLeod R: Identification of T. gondii epitopes, adjuvants, and host genetic factors that influence protection of mice and humans. Vaccine 2010, 28:3977–3989.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Panina-Bordignon P, Tan A, Termijtelen A, Demotz S, Corradin G, Lanzavecchia A: Universally immunogenic T cell epitopes: promiscuous binding to human MHC class II and promiscuous recognition by T cells. Eur J Immunol 1989, 19:2237–2242.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chen YZ, Liu G, Senju S, Wang Q, Irie A, Haruta M, Matsui M, Yasui F, Kohara M, Nishimura Y: Identification of SARS-COV spike protein-derived and HLA-A2-restricted human CTL epitopes by using a new muramyl dipeptidederivative adjuvant. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2010, 23:165–177.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bertholet S, Ireton GC, Ordway DJ, Windish HP, Pine SO, Kahn M, Phan T, Orme IM, Vedvick TS, Baldwin SL, Coler RN, Reed SG: A Defined Tuberculosis Vaccine Candidate Boosts BCG and Protects Against Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Transl Med 2010, 2:53ra74.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- O'Hagan DT, Tsai T, Reed S: Emulsion-Based Adjuvants for Improved Influenza Vaccines. Influenza Vaccines for the Future 2011, in press.Google Scholar

- Reed SG, Bertholet S, Coler RN, Friede M: New horizons in adjuvants for vaccine development. Trends Immunol 2009, 30:S23–32.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Persing DH, Coler RN, Lacy MJ, Johnson DA, Baldridge JR, Hershberg RM, Reed SG: Taking toll: lipid A mimetics as adjuvants and immunomodulators. Trends Microbiol 2002, 10:S32–37.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Deliyannis G, Jackson DC, Ede NJ, Zeng W, Hourdakis I, Sakabetis E, Brown LE: Induction of long-term memory CD8(+) T cells for recall of viral clearing responses against influenza virus. J Virol 2002, 76:4212–4221.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- BenMohamed L, Wechsler SL, Nesburn AB: : Lipopeptide vaccines--yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Lancet Infect Dis 2002, 2:425–431.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zeng W, Ghosh S, Lau YF, Brown LE, Jackson DC: Highly immunogenic and totally synthetic lipopeptides as self-adjuvanting immunocontraceptive vaccines. J Immunol 2002, 169:4905–4912.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chua BY, Zeng W, Jackson DC: Synthesis of toll-like receptor-2 targeting lipopeptides as self-adjuvanting vaccines. Methods Mol Biol 2008, 494:247–261.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tsunoda I, Sette A, Fujinami RS, Oseroff C, Ruppert J, Dahlberg C, Southwood S, Arrhenius T, Kuang LQ, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Ishioka GY: Lipopeptide particles as the immunologically active component of CTL inducing vaccines. Vaccine 1999, 17:675–685.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Brown CR, McLeod R: Class I MHC genes and CD8+ T cells determine cyst number in Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Immunol 1990, 145:3438–3441.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gazzinelli RT, Hakim FT, Hieny S, Shearer GM, Sher A: Synergistic role of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in IFN-gamma production and protective immunity induced by an attenuated Toxoplasma gondii vaccine. J Immunol 1991, 146:286–292.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gazzinelli R, Xu Y, Hieny S, Cheever A, Sher A: Simultaneous depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes is required to reactivate chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii . J Immunol 1992, 149:175–180.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Livingston BD, Alexander J, Crimi C, Oseroff C, Celis E, Daly K, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV, Fikes J, Chesnut RW, Sette A: Alterred helper T lymphocyte function associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and its role in response to therapeutic vaccination in humans. J Immunol 1999, 162:3088–3095.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alexander J, Fikes J, Hoffman S, Franke E, Sacci J, Appella E, Chisari FV, Guidotti LG, Chesnut RW, Livingston B, Sette A: The optimization of helper T lymphocyte (HTL) function in vaccine development. Immunol Res 1998, 18:79–92.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Alexander J, Oseroff C, Dahlberg C, Qin M, Ishioka G, Beebe M, Fikes J, Newman M, Chesnut RW, Morton PA, Fok K, Appella E, Sette A: A decaepitope polypeptide primes for multiple CD8+ IFN-gamma and Th lymphocyte responses: evaluation of multiepitope polypeptides as a mode for vaccine delivery. J Immunol 2002, 168:6189–6198.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Debierre-Grockiego F, Campos MA, Azzouz N, Schmidt J, Bieker U, Resende MG, Mansur DS, Weingart R, Schmidt RR, Golenbock DT, Gazzinelli RT, Schwarz RT: Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by glycosylphosphatidylinositols derived from Toxoplasma gondii . J Immunol 2007, 179:1129–1137.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Kim SK, Karasov A, Boothroyd JC: Bradyzoite-specific surface antigen SRS9 plays a role in maintaining Toxoplasma gondii persistence in the brain and in host control of parasite replication in the intestine. Infect Immun 2007, 75:1626–1634.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saeij JP, Arrizabalaga G, Boothroyd JC: A cluster of four surface antigen genes specifically expressed in bradyzoites, SAG2CDXY, plays an important role in Toxoplasma gondii persistence. Infect Immun 2008, 76:2402–2410.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Saeij JP, Boyle JP, Grigg ME, Arrizabalaga G, Boothroyd JC: Bioluminescence imaging of Toxoplasma gondii infection in living mice reveals dramatic differences between strains. Infect Immun 2005, 73:695–702.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Moutaftsi M, Peters B, Pasquetto V, Tscharke DC, Sidney J, Bui HH, Grey H, Sette A: A consensus epitope prediction approach identifies the breadth of murine T(CD8+)-cell responses to vaccinia virus. Nat Biotechnol 2006, 24:817–819.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Gulukota K, Sidney J, Sette A, DeLisi C: Two complementary methods for predicting peptides binding major histocompatibility complex molecules. J Mol Biol 1997, 267:1258–1267.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sidney J, Assarsson E, Moore C, Ngo S, Pinilla C, Sette A, Peters B: : Quantitative peptide binding motifs for 19 human and mouse MHC class I molecules derived using positional scanning combinatorial peptide libraries. Immunome Res 2008, 4:2.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Sidney J, Southwood S, Oseroff C, del Guercio MF, Sette A, Grey HM: Chapter 18, Measurement of MHC/peptide interactions by gel filtration. Curr Protoc Immunol 2001, Chapter 18:Unit 18.13.Google Scholar

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH: Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol 1973, 22:3099–3108.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

Copyright

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.