TAP Hunter: a SVM-based system for predicting TAP ligands using local description of amino acid sequence

- Proceedings

- Open Access

TAP Hunter: a SVM-based system for predicting TAP ligands using local description of amino acid sequence

https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-7580-6-S1-S6

© Tong et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2010

- Published: 27 September 2010

Abstract

Background

Selective peptide transport by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) represents one of the main candidate mechanisms that may regulate the presentation of antigenic peptides to HLA class I molecules. Because TAP-binding preferences may significant impact T-cell epitope selection, there is great interest in applying computational techniques to systematically discover these elements.

Results

We describe TAP Hunter, a web-based computational system for predicting TAP-binding peptides. A novel encoding scheme, based on representations of TAP peptide fragments and composition effects, allows the identification of variable-length TAP ligands using SVM as the prediction engine. The system was rigorously trained and tested using 613 experimentally verified peptide sequences. The results showed that the system has good predictive ability with area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AROC) ≥0.88. In addition, TAP Hunter is compared against several existing public available TAP predictors and has showed either superior or comparable performance.

Conclusions

TAP Hunter provides a reliable platform for predicting variable length peptides binding onto the TAP transporter. To facilitate the usage of TAP Hunter to the scientific community, a simple, flexible and user-friendly web-server is developed and freely available at http://datam.i2r.a-star.edu.sg/taphunter/.

Keywords

- Support Vector Machine

- Human Leukocyte Antigen

- Human Leukocyte Antigen Class

- Transporter Associate With Antigen Processing

- Presentation Pathway

Background

The binding of peptides to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules is a prerequisite for CD8+ T cell response. Majority of these peptides are generated in the cytosol by proteosomal cleavage of endogenous proteins [1]. The degraded peptides, preferably 9-18 amino acids in length, are transported into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) for loading on HLA class I molecules [2, 3]. The ligated HLA class I complexes then leave the ER and are transported to the cell surface for presentation to T cell receptors [4]. Defects in TAP genes can severely impair peptide transport into the ER, and result in reduced surface expression of HLA class I molecules [5].

The substrate specificity of TAP has been examined in several studies. It is now known that hydrophobic aromatic residues are preferred at the C-terminus, positions (p) 3, and p7; hydrophobic or positively charged residues are preferred at p2; aromatic or acidic residues are preferred at p1; and proline is disfavored at p1 and p2 [5, 6, 7]. Different HLA class I alleles exhibit different TAP-dependencies. HLA-A2 is reportedly the least TAP-dependent; B7 can bind to other mechanisms besides TAP transport; while A3 is predominantly TAP dependent [8]. As such, improved understanding of TAP selectivity is important for elucidating its role in regulating the supply of peptides to HLA class I molecules. This is also crucial for the design of T cell-based vaccines for infectious diseases, autoimmune disorders, transplantation and cancer.

To date, a variety of computational methods have been developed to predict TAP-binding peptides. Daniel and coworkers [9] applied artificial neural networks (ANN) to simulate TAP binding experiments. Zhang et al. [10] combined ANN and hidden Markov models to predict peptide binding to human TAP. Doytchinova and colleagues [11] developed an additive QSAR model for peptides binding to TAP molecule. Bhasin and Raghava [12] utilized a cascade support vector machines (SVM)-based method to predict the binding affinities of TAP ligands, while Peters et al. [13] and Diez-Rivero et al. [14] reported the use of stabilized matrix method and SVM-based system, respectively, to predict both nonamer and variable length TAP ligands. Although numerous studies have shown the importance of sequence locality in TAP transport [12], none of the existing systems have exploited localized amino acid effect for predicting TAP binding affinity of peptides.

Here we report TAP Hunter, a web-based computational system for predicting TAP ligands using SVM as the discrimination engine. A novel data encoding scheme, based on sequence locality and composition effects, allows the system to model essential features in peptides that can bind to the TAP translocator. This simple method allows us to predict TAP ligands with an accuracy that is better than existing approaches based on full-length sequences.

Methods

Data

Performance evaluation of SVM models using different peptide localities (selected outputs are shown)

No of a.a. |

Model No. |

a.a. positions used in modeling |

ACC |

AROC |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5-fold CV |

Independent testing |

5-fold CV |

Independent testing |

|||

1 |

2, 3 |

0.80 |

0.76 |

0.80 |

0.75 |

|

2 |

2 |

2, 9 |

0.76 |

0.77 |

0.80 |

0.83 |

3 |

3, 9 |

0.79 |

0.78 |

0.81 |

0.86 |

|

4 |

1, 2, 3 |

0.79 |

0.77 |

0.83 |

0.78 |

|

3 |

5 |

1, 2, 9 |

0.82 |

0.82 |

0.88 |

0.86 |

6 |

1, 3, 9 |

0.80 |

0.77 |

0.84 |

0.85 |

|

7 |

2, 3, 9 |

0.82 |

0.83 |

0.87 |

0.88 |

|

8 |

1, 2, 3, 7 |

0.79 |

0.73 |

0.84 |

0.76 |

|

9 |

1, 2, 3, 8 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.82 |

0.77 |

|

10 |

1, 2, 3, 9 |

0.84 |

0.82 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

|

11 |

1, 2, 7, 9 |

0.81 |

0.75 |

0.87 |

0.83 |

|

4 |

12 |

1, 2, 8, 9 |

0.80 |

0.78 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

13 |

1, 3, 7, 9 |

0.81 |

0.79 |

0.85 |

0.86 |

|

14 |

1, 3, 8, 9 |

0.82 |

0.81 |

0.83 |

0.86 |

|

15 |

2, 3, 7, 9 |

0.83 |

0.76 |

0.89 |

0.83 |

|

16 |

2, 3, 8, 9 |

0.78 |

0.82 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

|

17 |

1, 2, 3, 7, 8 |

0.79 |

0.76 |

0.84 |

0.74 |

|

18 |

1, 2, 3, 8, 9 |

0.81 |

0.82 |

0.86 |

0.89 |

|

5 |

19 |

1, 2, 7, 8, 9 |

0.82 |

0.76 |

0.87 |

0.83 |

20 |

1, 2, 3, 7, 9 |

0.82 |

0.77 |

0.88 |

0.86 |

|

21 |

1, 3, 7, 8, 9 |

0.80 |

0.80 |

0.85 |

0.83 |

|

22 |

2, 3, 7, 8, 9 |

0.82 |

0.79 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

|

23 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

0.76 |

0.8 |

0.83 |

0.80 |

|

6 |

24 |

1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9 |

0.82 |

0.79 |

0.85 |

0.86 |

25 |

4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

0.78 |

0.69 |

0.80 |

0.59 |

|

26 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9 |

0.80 |

0.75 |

0.85 |

0.84 |

|

7 |

27 |

1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9 |

0.81 |

0.76 |

0.85 |

0.86 |

28 |

1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

0.81 |

0.77 |

0.86 |

0.84 |

|

29 |

1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

0.81 |

0.82 |

0.86 |

0.85 |

|

8 |

30 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

0.80 |

0.80 |

0.85 |

0.84 |

31 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 |

0.78 |

0.79 |

0.83 |

0.85 |

|

9 |

32 |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

0.79 |

0.78 |

0.84 |

0.83 |

Support vector machines

α i is solved by quadratic programming subjected to 0≤ α i ≤C condition, where C is the parameter to control the trade-off between the margin and training error. K represents the kernel function while sgn is the sign of the argument in the form of -1 or 1. If the function of a test instance is greater than zero, it will be tagged as positive case while a function value of less than zero is presented as negative case. This concept of kernel function mapping allows SVM to model very complex precincts and thus enable SVMs to easily handle non-linear data. Though there are many different type kernels proposed by researchers, the commonly used and broadly relevance to many applications are the linear, polynomial, radial basis functions and sigmoid kernel functions.

Model building and evaluation

TAP Hunter was implemented using the SVM-Light package [17]. The system employs the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel for SVM training. We also explored linear and polynomial kernel functions but they did not achieve higher performance levels (data not shown). The inputs to the SVM are binary strings or feature vectors representing encoded representations of physicochemical properties previously reported as significant for TAP binding [12]. These include hydrophobicity, aromaticity, charges and residue weight. It has been reported that the N- and C-terminal residues of TAP ligands contribute to most of the binding interactions [12]. Using the above features, truncation analysis was performed to examine the contribution of each and every peptide position to binding. 5-fold cross-validation (CV) was performed to assess the stability of the derived models. Finally, the performance of each models were assessed using sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), accuracy (ACC) and the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AROC) as previously described [18].

Results

System performance

The robustness of TAP Hunter using different sequence localities as inputs for training has been estimated for 5-fold CV (Table 1). The best model was achieved using descriptors derived from peptide positions N+1, N+2, N+3 and C (model 10; ACC=0.84 and AROC=0.82 for 5-fold CV; ACC=0.88 and AROC= 0.88 for Testing dataset i), consistent with existing studies that these amino acid positions are crucial for binding [12].

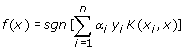

Comparison with existing methods

Mean AROC curve evaluation for various TAP predictors

p-values for the observed AROC difference between TAP Hunter and each of the existing TAP predictors for nonamers ligands predictions

TAPPred SVM |

TAPPred Cascade |

SMM |

TAPREG |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

TAP Hunter |

8.2x10-4 |

2.2x10-16 |

Not Significant |

5.1x10-8 |

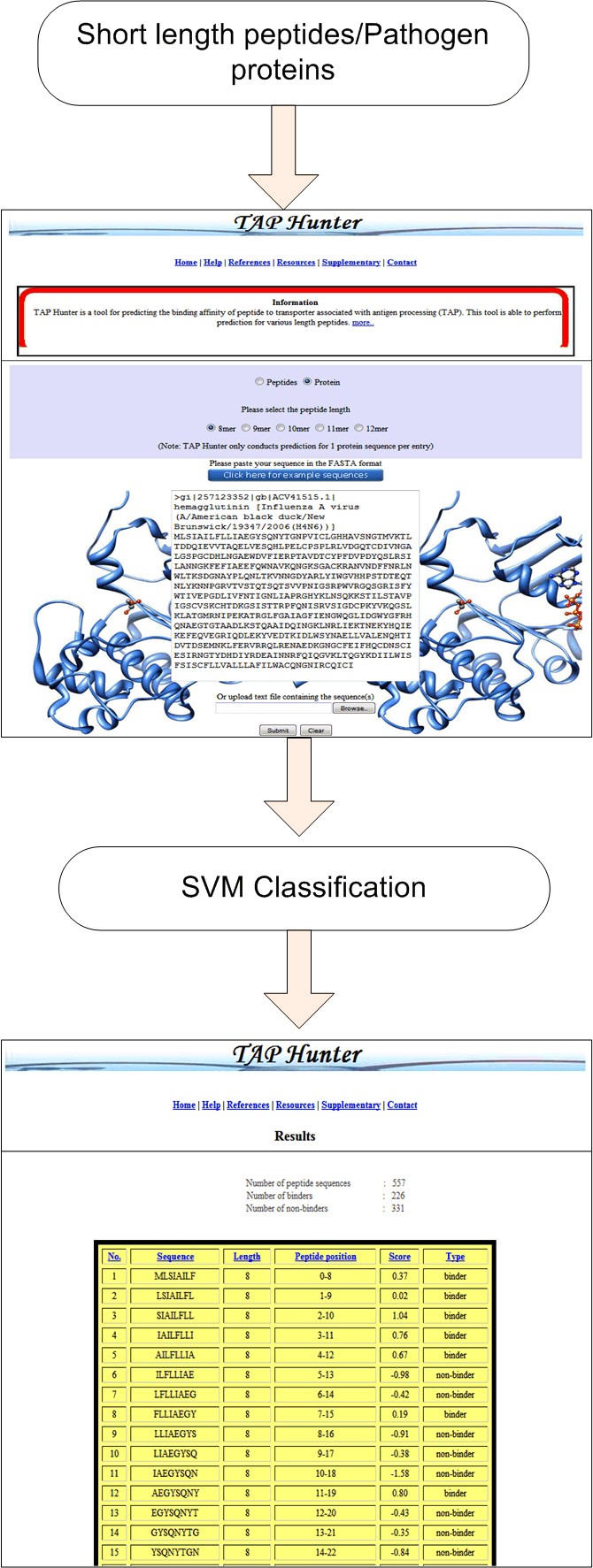

Web-server implementation and description

The execution of the TAP Hunter web-server comprises of two segments, the front and the back end. The front end, written in HTML and JavaScript, consists of the web-interface designed for user input sequence(s) as well as the references and databases used for the collection of the training and evaluation datasets. The back end administration is run by several modules (written in Perl, JavaScript, HTML, CGI and Java) for (i) the input sequence(s) error assessment, (ii) the cleavage of protein sequence into the user defined peptide length, (iii) the generation sequence feature vectors, the operation of SVM-light package and (iv) output of results. TAP Hunter has been rigorously tested on Internet Explorer (IE) and Mozilla Firefox browsers and is expected to perform on other major web browsers. Typically the processing time required to perform TAP-peptide binding affinity prediction operation for 566 nonamer peptides is less than 30 seconds.

Snapshot of the prediction process using TAP-HunterThe results are presented as a sortable table according to the selected parameters at the top.

Discussion and conclusion

The complex molecular mechanism involved in antigen processing and presentation pathway has impeded our capability to predict the adaptive nature of immune responses confidently. Discovery through experimental evaluation is expensive and time-consuming. Yet, usage of computational methods to complement laboratory experiments is likely to expedite the knowledge discovery in immunology. Particularly in recent years, we have seen increased attempts to simulate the cell-mediated immune system by integrating the proteasome, TAP, and HLA components of the antigen processing and presentation pathway [19, 20, 21, 22]. A study by Doytchinova and colleagues in 2004 has shown that TAP pre-selection could reduce the number of non-binders from 10% (TAP-independent) to 33% (TAP-dependent). In this aspect, TAP Hunter derives its feature vectors from the N- and C- terminal positions of TAP ligands that are known to exhibit binding motifs and most heavily influence the TAP binding affinity [5, 6, 7]. Our investigation has shown that this innovative solution is equally adept or even superior in discriminating nonamer TAP binding peptides than all current nonamer TAP predictors. Further refinement in the feature selection procedure may enable the development of TAP Hunter into a practical tool for pre-selecting T cell epitopes.

Declarations

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Engineering Research Council (SERC) of A*STAR.

This article has been published as part of Immunome Research Volume 6 Supplement 1, 2010: Ninth International Conference on Bioinformatics (InCoB2010): Immunome Research. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.immunome-research.com/supplements/6/S1.

Authors’ Affiliations

References

- Ritz U, Seliger B: The transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP): structural integrity, expression, function, and its clinical relevance. Mol. Med. 2001, 7: 149-158.PubMed CentralPubMedGoogle Scholar

- Heemels MT, Ploegh HL: Substrate specificity of allelic variants of the TAP peptide transporter. Immunity. 1994, 1: 775-784. 10.1016/S1074-7613(94)80019-7.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- van Endert PM, Tampé R, Meyer TH, Tisch R, Bach JF, McDevitt HO: A sequential model for peptide binding and transport by the transporters associated with antigen processing. Immunity. 1994, 1: 491-10.1016/1074-7613(94)90091-4.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lefranc MP, Lefranc G: The T cell receptor facts book. 2001, Academic Press. LondonGoogle Scholar

- Lankat-Buttgereit B, Tampé R: The transporter associated with antigen processing: function and implications in human diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82: 187-204.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- van Endert PM, Riganelli D, Greco G, Fleischhauer K, Sidney J, Sette A, Bach JF: The peptide-binding motif for the human transporter associated with antigen processing. J. Exp. Med. 1995, 182: 1883-1895. 10.1084/jem.182.6.1883.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Uebel S, Kraas W, Kienle S, Wiesmüller KH, Jung G, Tampé R: Recognition principle of the TAP translocator disclosed by combinatorial peptide libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997, 94: 8976-8981. 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8976.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larsen MV, Nielsen M, Weinzier A, Lund O: TAP-independent MHC class I presentation. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2006, 2: 233-245. 10.2174/157339506778018550.View ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Daniel S, Brusic V, Caillat-Zucman S, Petrovsky N, Harrison L, Riganelli D, Sinigaglia F, Gallazzi F, Hammer J, van Endert P: Relationship between peptide selectivities of human transporters associated with antigen processing and HLA class I molecules. J. Immunol. 1998, 161: 617-624.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Zhang GL, Petrovsky N, Kwoh CK, August JT, Brusic V: PredTAP: a system for prediction of peptide binding to the human transporter associated with antigen processing. Immunome Res. 2006, 2: 3-10.1186/1745-7580-2-3.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doytchinova I, Hemsley S, Flower DR: Transporter associated with antigen processing preselection of peptides binding to the MHC: a bioinformatics evaluation. J. Immunol. 2004, 173: 6813-6819.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bhasin M, Raghava GP: Analysis and prediction of affinity of TAP binding peptides using cascade SVM. Protein Sci. 2004, 13: 596-607. 10.1110/ps.03373104.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Peters B, Bulik S, Tampe R, van Endert PM, Holzhütter HG: Identifying MHC class I epitopes by predicting the TAP transport efficiency of epitope precursors. J Immunol. 2003, 171: 1741-1749.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Diez-Rivero CM, Chenlo B, Zuluaga P, Reche PA: Quantitative modeling of peptide binding to TAP using support vector machine. Protein. 2009, 10: 1002-1012.Google Scholar

- Lata S, Bhasin M, Raghava GP: MHCBN 4.0: A database of MHC/TAP binding peptides and T-cell epitopes. BMC Research Notes. 2009, 2: 61-67. 10.1186/1756-0500-2-61.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Weinzierl AO, Rudolf D, Hillen N, Tenzer S, van Endert PM, Schild H, Rammensee HG, Stevanović S: Features of TAP-independent MHC class I ligands revealed by quantitative mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38: 1503-1510. 10.1002/eji.200838136.View ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Joachims T: Making large-Scale SVM learning practical. Advances in Kernel Methods - Support Vector. Edited by: Scholkopf,B. 1999, MIT-Press, Cambridge MA, 42-56.Google Scholar

- Muh HC, Tong JC, Tammi MT: AllerHunter: a SVM-pairwise system for assessment of allergenicity and allergic cross-reactivity in proteins. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4: e5861-10.1371/journal.pone.0005861.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Doytchinova IA, Guan P, Flower DR: EpiJen: a server for multi-step T cell epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006, 7: 131-142. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-131.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Guan P, Doytchinova IA, Zygouri C, Flower DR: MHCPred: bringing a quantitative dimension to the online prediction of MHC binding. Appl Bioinformatics. 2003, 2: 63-66.PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M: Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007, 8: 424-10.1186/1471-2105-8-424.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Dönnes P, Kohlbacher O: Integrated modeling of the major events in the MHC class I antigen processing pathway. Protein Sci. 2005, 14: 2132-2140. 10.1110/ps.051352405.PubMed CentralView ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

Copyright

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.